Long-time Bay Area pal Hugo Eccles is co-founder and design director of Untitled Motorcycles (UMC). With workshops in San Francisco and London, UMC designs and builds custom motorcycles for individual clients and in partnership with factory brands like Ducati, Triumph, Yamaha, Zero, Harley-Davidson, and Moto Guzzi. He’s been a friend since early 2015, when Henri and I rode 41 miles up the 101 to his original workspace at the old Moto Guild location on De Haro Street across from Anchor Brewing Company.

Alongside running UMC in San Francisco, the British expat is a professional industrial designer who has worked for a wide variety of clients, including Nike, Ford, and TAG Heuer. Hugo recently curated and designed the MOTO MMXX motorcycle exhibition at San Francisco’s Museum of Craft and Design.

On the 100th anniversary of Moto Guzzi, I asked him a few open-ended questions about the Italian maker; I left all his British English spellings intact because it’s charming.

Q: As a designer, rider and custom builder, what attracted you to Moto Guzzi?

I've always had a soft spot for the iconic Guzzi transverse V-twin and the classic Tonti frame. For me, a classic Moto Guzzi is the quintessential motorcycle. It’s what you imagine when you think “motorcycle”.

There’s something very evocative—and exciting—about the way the cylinders poke out like the Guzzi’s do. I think it’s because it invites you to interact with the motor in a way that’s almost unique to Moto Guzzi.

When you’re riding a Guzzi, you inevitably end up resting your knee on the valve cover or, in cold weather, using them to warm your hands while waiting at the lights, like petting the shoulder of a mechanical beast. Because of the transverse layout, a Guzzi rocks side-to-side as it’s idling. It feels alive, and when you rev it you can feel the whole motorcycle twist under you.

From a design perspective, I love the look of the Guzzi’s large block motor. It’s unpretentious in its practicality. It sounds like a strange thing for a designer to say but I can’t stand motorcycles that have been over-designed, where the ‘design’ has been applied so heavy-handedly.

The Guzzi is both generic and characteristic — a very difficult balance to strike. As a designer, I spend an inordinate amount of time trying to make it look like I did nothing, trying to make the end result appear as natural and effortless as possible, and that’s the quality that a Moto Guzzi has. It has a beautiful inevitability to it, as if it always had to be that way.

Q: Tell me about all the Moto Guzzis you customized: which model/year they began as, when you began/finished each project.

I’ve worked on a number of Guzzi projects over the years but two in particular stand out: the ‘Supernaturale’ and the ‘Fat Tracker’.

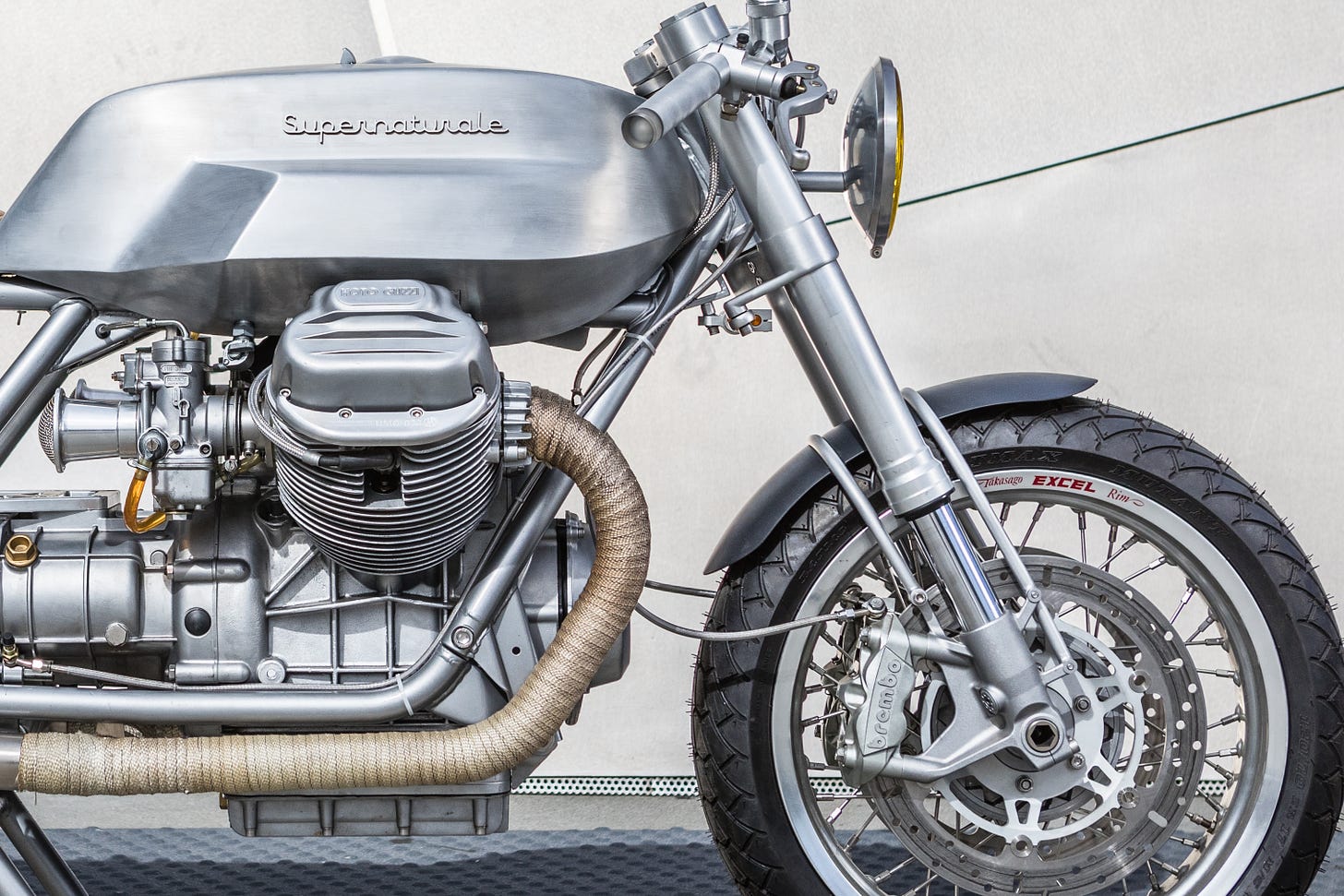

The ‘Supernaturale’ was built on a 1975 Moto Guzzi 850T that my client sourced from a seller in Texas, and had shipped to San Francisco with the plan of building the ultimate Guzzi Le Mans tribute.

‘Supernaturale’ is a mix of original and modern parts carefully finished so they blend together seamlessly. I’d intended to use an original Le Mans tank but the shape didn’t match my expectations so I convinced my client that, instead, we should build the Le Mans tank that existed in our imaginations — something longer, lower, wider, and integrated with the beautiful V-twin motor.

I built a full-scale tank buck on the stripped 850T frame and, from that, made templates for the hand-formed aluminium tank. A 1960’s flip-top gas cap was frenched into the top surface and ‘Supernaturale’ logos were laser-cut from aluminium, anodized gold, then rubbed back to reveal the original material.

The wheel hubs are from the original `70s bike laced with new stainless steel spokes to modern Takasago Excel 17” rims. My client had fallen in love with Dunlop Sportmax Mutants which, at the time, were impossible to source in the States so his friend brought them over on his flight as hand luggage.

I specified the widest tyre I could for the rear—a 150/60-17—which meant I had to notch the swingarm driveshaft leaving about 1/8” clearance (but, clearance is clearance). The rear wheel is supported by twin Fournales air shocks, originally designed for light aircraft, which hide discreet LED ring blinkers on each side. The original Tonti frame was tidied up and a rear hoop, sourced from an earlier ‘loop frame’ Guzzi, added into which was cut a channel for a grey-tinted LED tail/brake light strip.

The original front hub was modified to carry twin brake rotors (custom-made by EBC) and paired with modern Showa USD forks and Brembo monobloc calipers from a late-model Suzuki GSX-R750, linked to new Magura radial masters. The forks are held by custom-designed brackets, the upper incorporating a Motogadget display and flush-mounted LED indicator lights, with engraved labels in Italian, mimicking the 1970s original. The CNC’d brackets were laboriously finished by hand and then media blasted to give them a softer, more period-appropriate appearance.

Likewise with the minimal knurled handlebars containing an internal throttle mechanism, bar-end blinkers (which was a bear to wire past the internal throttle), and hidden fingertip-buttons, all linked to a modern electrical system. The headlight was a 2” thin 1960s Cibie rally fog lamp, with original yellow cast glass lens, sourced from a dealer in France.

The engine was stripped, overhauled with new bearings, polished and balanced crankshaft. While we were in there, I had the cylinders re-lined with Nikasil, the flywheel lightened by 8 pounds, and upgraded the clutch plates. A modern internal oil filter was added (the original had what can be best described as an “oil strainer”), and rubber oil lines were replaced with braided stainless steel.

The engine was braced to the frame by a pair of custom-designed brackets that stiffened the motorcycle, and improved overall handling. The original 30mm carbs were enlarged to Dellorto PHF-36’s paired with beautiful Malossi alloy trumpets with domed mesh guards. The exhaust was a custom setup with removable internal baffles behind the nickel-plated end pipes. The ‘Supernaturale’ ended up being a surprisingly lightweight bike at 394 pounds — 23% lighter than the 1970s original and the same dry weight as a Suzuki GSX-R750.

The name ‘Supernaturale’ came from the idea that all the materials on the motorcycle were in their raw, natural, state: the motor had been media blasted to its original alloy, the handmade tank fabricated in brushed bare aluminium, the seat upholstered in raw leather, and so on.

All the materials were intended to patina beautifully with use: the untreated leather became darker with age, the tank sides were polished by the rider’s knees, evidence of wear-and-tear accumulated, and the ‘character’ of the motorcycle emerged. The whole thing was intended to feel very effortless and natural — sprezzatura with some wabi-sabi mixed in for good measure.

‘Supernaturale’ was completed early in the morning of May 6 2017, just before it was loaded into a van and driven 125 miles to the Quail Motorcycle Gathering in Carmel, California, where it won the coveted overall ‘Design & Style’ Award.

The ‘Fat Tracker’ started life as a 2017 Moto Guzzi V9 Bobber for a project commissioned by Moto Guzzi Americas as part of their ‘Pro Build’ programme. Brand commissions are somewhat different from private commissions in that I generally have a greater degree of creative freedom. I’d intentionally picked the ‘Bobber’ version over the ‘Roamer’ because I liked the Bobber’s fat wheels and had suggested to Guzzi an idea of some sort of dune bike with a sand whip, paddle tyres: the works.

Typical with most projects, I started by stripping the Bobber down to the rolling chassis—frame motor, and wheels—to see what I had to work with. The V9 had a lovely Tonti-style tubular frame and the rear of the frame, where it supported the engine, suggested the outline of a racing number plate. That seeded the idea of a fat-wheeled flat tracker, aka ‘Fat Tracker’.

I decided to work with the original 16" cast alloy wheels because the shaft drive made swapping the rear end tricky. Little did I know that it was near impossible to find cool wide off road-style tyres for 16” wheels. I eventually opted for 140/70-16 Heidenau K66s both front and rear which could be interchanged with each other à la flat track. The K66s were actually all-weather scooter tyres but rated to 112 mph and 639 pounds so they were more than adequate for the V9.

I cleaned up the frame, removing unwanted brackets, and moved the rear suspension mounts forward an inch to tidy up the aesthetics. A custom rear hoop continued the flow of the frame and also provided a seat bump stop. A large semicircular LED rear light incorporated the tail light, brake light and blinkers.

The V9's air-cooled 853cc motor is torquey so it's well suited to dirt. I liked the idea of creating a tension between the large transverse V-twin motor and a small, slim monobody perched on top. It reminded me of the Hanna-Barbera character Magilla Gorilla—a large ape with a tiny hat—and he became the project mascot, eventually appearing on the gas tank. The Fat Tracker actually has two tanks — a visible upper tank (which holds 1.2 gallons) and an inconspicuous lower tank (1.7 gallons) hidden under the gearbox which contains the fuel pump. Combined they give the Fat Tracker a respectable 100+ mile range.

To protect the rider’s legs from the high-mounted custom exhaust, it was ceramic coated and wound in heat-absorbing wrap. Above the wrap was a carbon fibre shield, itself lined with a mirrored heat reflector, and then a pair of perforated aluminium heat shields which integrated with the bodywork. Perforated exhaust tips mimic the heat shield's hole pattern.

The aluminium shields were a task in themselves: 438 holes, each of which needed to be punched, piloted, drilled and reamed before being filed, sanded, and finally media blasted - about 2,200 operations in all. I’ll probably build them differently next time.

I was a bit nervous about how well all those layers of ceramic-wrap-reflector-carbon-aluminium were going to work and I bought a pair of aluminised kevlar-lined firefighter trousers for the test ride. As it turned out, the five layers of heat shielding worked fine, even in the heat of California. I still have the trousers.

The build quality on the V9 motor was really good so I kept it in the factory-spec black finish. All the mechanical and control elements were finished in various textures of black to create a visual separation from the bodywork.

For the body, I wanted to use a colour that was both contemporary and classically 'Guzzi'. Inspired by the iconic 1971 V7 Sport’s green 'Verde Legnano' bodywork and red 'Telaio Rosso' frame, I spec’d a bespoke Kandy Kolor iridescent paint that constantly shifts from metallic yellow to metallic green. A bright red accent colour runs along the underside of the frame and kicks up to blend with the LED brake/blinker array at the rear.

For the front, I designed a DTRA-inspired illuminated number plate with a pair of stacked LED spotlights that performed as hi/lo-beams. Behind the headlight, the controls were completely replaced with custom switches wired inside modified Suzuki GSXR clipons (mounted upside down and backwards), paired with Oury grips and Magura HC1 radial masters. I kept the original top bracket and machined holes for the flush-mounted Motogadget LED display, and a bright red start button.

‘Fat Tracker’ was finished on November 16, 2017 before I drove 420 miles to Moto Guzzi’s headquarters in Costa Mesa, California for a film and photo shoot. The following days me and the Fat Tracker were on the Moto Guzzi stand at the 2017 International Motorcycle Show at Long Beach, California.

The ‘Fat Tracker’ weighs in at only 349 pounds, 86 pounds lighter than the original bike. It’s an incredibly fun bike to ride and, with its chunky tyres, has a real `80s California beach buggy vibe to it. I’m looking forward to playing with that on future versions – fiberglass monobody, candy flake paint, Hella headlights, and so on.