Northern California’s ongoing ‘bomb cyclone’ (biblical rain and high winds) since early January got me restless. This – coupled with enjoying my first kidney stone experience through most of December – made answering riding pal Brian’s invitation to join him on his annual four-day Death Valley ride a no-brainer, 1,200-plus miles of chasing Brian’s 2018 Triumph Tiger 800 Adventure on my 2000 Moto Guzzi Quota 1100 ES nearly one year after buying it from McInnis.

I’ve followed Brian on several Sierra rides for five years, but never the southern loop into Death Valley, a place so sinister-sounding it’s not surprising neither have several of my riding pals.

“Too often I would hear men boast of the miles covered that day, rarely of what they had seen.”

— Louis L’Amour

The original departure date was March 11, but Mother Nature decided to zap our region of the country with a Darth Sidious-vicious soaking, bumping it out another week. The replacement front brake rotors I ordered in April 2022 just arrived from MG Cycle, so a quick and easy session with some Replacements on the workshop’s speakers after some mods to the kickstand and saddlebags were in order. Brian also thought it wise for me to add my Rotopax gas container in case we went a bit too long between remote gas stations; I found my disc mount and hardware and drilled a couple holes to install it on the top case’s platform.

After our grand trip to Mammoth Lakes in the Eastern Sierras last late May, I replaced my 50/50 Heidenau K60 Scout tires with Continental Trail Attack 3s, mainly to be equally yoked with Brian’s penchant for the same because he loves to scoot on asphalt and not so much on dirt. I also wore down my Heidenaus in less than 2,000 miles, compared to 7,000-plus on Contis, Michelin or Dunlop street rubber. Grip is important.

Our weather forecast called for a mix of early morning temps in the low 40s to mid 50s and low 50s to mid 60s mid afternoon, with an ever-changing prediction for rain that wreaked havoc on best-laid plans (anyone else frustrated with modern apps and the lack of commitment to a concrete forecast? Whatever happened to a proper Doppler reading? Sheesh.).

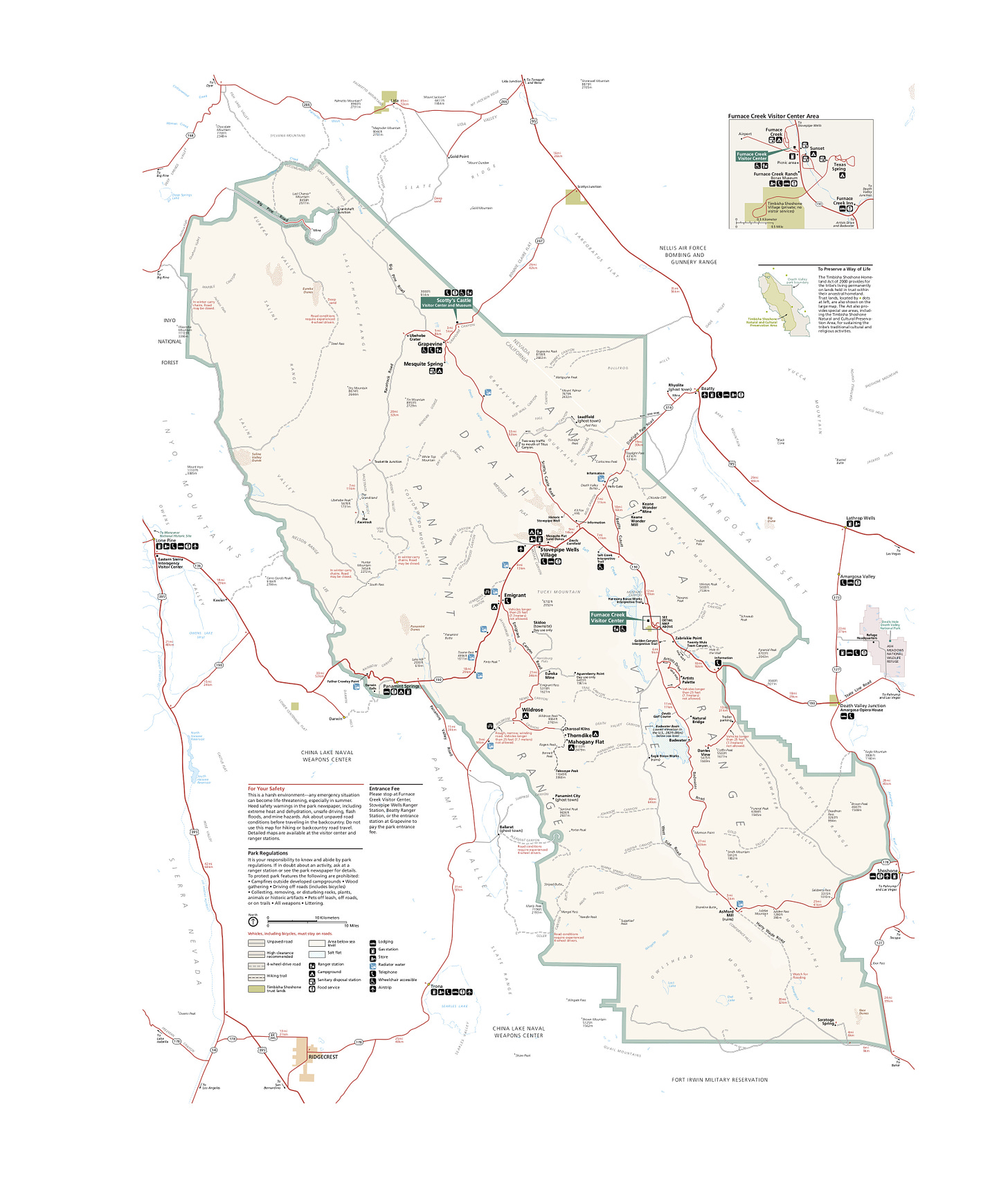

Death Valley National Park

Death Valley became a national monument in 1933 and is known for being the hottest, lowest, and driest location in the country. The parched landscape rises into snow-capped mountains and is home to the Timbisha Shoshone people, with 3.4 million acres stretching across California and Nevada. The top of Telescope Peak is 11,049 feet high; the lowest point is -282 feet at Badwater Basin. In 2018, nearly 1.7 million people visited the park, a new visitation record.

Gearing Up For Hell

Not wanting to be left unprepared before too much grass grew under my feet, I spent the past few months researching and choosing upgraded gear for our 2023 adventures. A white Bell Adventure MX-9 Mips helmet with ProTint shield was first, followed by REV’IT! Valve H20 waterproof laminated leather/textile jacket and pants, with REV’IT! Link GTX waterproof boots.

In My Cases

My packing list included thin Merino wool short- and long-sleeve tops and socks – ideal for cold or warm weather – plus a Stylmartin neck gaiter, Dainese balaclava and three sets of gloves: warm weather, intermediate/cold, wet/cold. My go-to black Crocs, Plexus plastic cleaner with soft cloth, head lamp, iPhone, Rapha winter jersey, Dainese kidney belt, Belstaff vest, Stellar beanie, wallet, Caddis Porgy readers, toiletries, snack food, Sightglass instant coffee, water bottle, two books, notebook, tool roll, electronic charger/cords, bandanas, sunglasses, one pair of shorts, Adidas sweats, two t-shirts and Duluth underwear filled the remainder of my top and side cases.

Day One: San Jose to Bakersfield

We met at the Shell station on Bernal Road where CA-85 and 101 intersect in south San Jose around 8 am on Saturday. I fueled up and adjusted the shifter peg to accommodate the taller toe box height of the REV’IT! boots, and we were off, cruising south on 101 to 152 East, taking Pacheco Pass located in the Diablo Range in southeastern Santa Clara County. Pacheco Pass is the main route through the hills separating the Santa Clara Valley and the Central Valley, where we continued to Los Banos after viewing a rather full San Luis Reservoir and benefiting from low cross winds.

Day One was destination Bakersfield, skirting the Sierra Foothills (above) through the western shores of Pine Flat Lake, east of Fresno, where the rough roads turn to goat paths and climb, climb, climb. Heavy rains had washed away several sections of road in the Yokohl Valley (below), with several ROAD CLOSED signs warning ne’er-do-wells off. We proceeded with caution, picking through the debris ever forward, undaunted and determined, arriving at the Bakersfield DoubleTree Inn in time for dinner.

Day Two: Bakersfield to Furnace Creek

Brian was hedging our bets on decent weather taking CA-178 East, and while the skies were splotchy with swollen gray clouds it wasn’t raining when we departed in 55-degree conditions Sunday morning. The winds picked up as the temperature dropped through Kern Canyon, with a rushing Kern River to our left and steep rocky hills looking like Scotland on both sides. The clouds began shedding tears from heaven as the tarmac rolled by, which sadly darkened my maiden voyage past Isabella Lake.

Just beyond unincorporated Onyx, the rain turned to snow as the temperature dropped to 30 or so on Walker Pass. Heavy rain returned as we turned left on CA-14, which dovetails into CA-395 North toward the popular ski and snowboard destination Mammoth Lakes.

As the rain beat down faster than a Neil Peart drum solo, we found shelter, warmth, snacks and gas at a Shell station just south of Pearsonville, watching a parade of L.A.’s beautiful snow bunnies do the same. I swapped out my intermediate/cold gloves for wet/cold as we continued north on 395, heading east on CA-190 just beyond Gus’s Fresh Jerky. We rolled along at a good clip with little or no traffic, turning right at the CA-136 junction. Death Valley was approaching fast with every tight radius curve, opening up a sight for sore/tired eyes as we stopped for a vista view at the Father Crowley Overlook (below).

We gained and lost much elevation on our final stretch into Furnace Creek, arriving at The Ranch at Death Valley by 3 pm. With extra time before check-in, we filled up our tanks and our stomachs before riding out to Badwater Basin 18 miles south, and at 282 feet below sea level, the lowest point in North America. On our return Brian wanted to check out a few scenic detours, starting with a 1.5-mile deeply washboarded road to Natural Bridge; I turned around after 100 yards, calling bullshit after my decades-old fillings started coming loose. Brian soldiered on and after his return we checked out Artist’s Palette (below), where sea green, lemon yellow, periwinkle blue and salmon pink mineral deposits are splashed across the barren background like brilliant dabs of paint from a giant’s brush. This time the twisty road was gloriously paved.

We returned to The Ranch, checked in, had an overpriced buffet dinner ($35 each - ouch) and stayed up talking about what we’d experienced and what was to come the following day.

Day Three: Furnace Creek to Ridgecrest

We enjoyed an extra hour of sleep, rising around 7 am. I brought Sightglass instant coffee and made two cups while we ate some energy bars for breakfast. The plan was to enjoy more of the nearby scenery before heading west.

Doubling back toward Badwater, we stayed on CA-190 East to Furnace Creek Wash Road, which in less than 30 minutes climbs to Dante’s View (above) 5,475 feet above the Valley with the final half-mile stretch topping off at 15 percent grade. This sweeping view of Death Valley was humbling, larger than life and a bit woozy inducing, if I’m being honest.

On our way back to check out of The Ranch we stashed my top case and Rotopax in some sagebrush at the exit of Twenty Mule Team Road (above), lightening my load and allowing me to enjoy a hard packed twisty one-way dirt road through the Twenty Mule Team Canyon, despite a Jack Black look alike in a rental van driving the wrong way. I gathered my gear at the exit and we stopped at Zabriskie Point (below) for more scenic viewing with the great unwashed before returning to Furnace Creek.

My ever-curious riding companion had more in store for us after we fueled up at $6.78 a gallon for premium in Furnace Creek, one of the last gas stations we’d see until Ridgecrest.

Rhyolite Ghost Town

Just beyond Beatty Junction is Daylight Pass Road, which we took to head northeast toward the Nevada border becoming 374. Our destination was Rhyolite (below), a ghost town that went bust before it could boom. Rhyolite in Nye County, in Nevada in the Bullfrog Hills about 120 miles northwest of Las Vegas, near the eastern boundary of Death Valley National Park. The town began in early 1905 as one of several mining camps that sprang up after a prospecting discovery in the surrounding hills. During an ensuing gold rush, thousands of gold-seekers, developers, miners and service providers flocked to the Bullfrog Mining District. Many settled in Rhyolite, which lay in a sheltered desert basin near the region's biggest producer, the Montgomery Shoshone Mine.

Industrialist Charles M. Schwab bought the Montgomery Shoshone Mine in 1906 and invested heavily in infrastructure, including piped water, electric lines and railroad transportation, that served the town as well as the mine. By 1907, Rhyolite had electric lights, water mains, telephones, newspapers, a hospital, a school, an opera house, and a stock exchange. Published estimates of the town's peak population vary widely, but scholarly sources generally place it in a range between 3,500 and 5,000 in 1907–08.

Rhyolite declined almost as rapidly as it rose. After the richest ore was exhausted, production fell. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the financial panic of 1907 made it more difficult to raise development capital. In 1908, investors in the Montgomery Shoshone Mine, concerned that it was overvalued, ordered an independent study. When the study's findings proved unfavorable, the company's stock value crashed, further restricting funding. By the end of 1910, the mine was operating at a loss, and it closed in 1911. By this time, many out-of-work miners had moved elsewhere, and Rhyolite's population dropped well below 1,000. By 1920, it was close to zero.

Most of the original buildings are gone or weather ravaged, shells of a better time. The Bottle House (below) is still standing, protected by a fence and holding on for dear life 100 years later.

Tourist attractions for the day were done, so we remounted our bikes to double back into Death Valley, hopping back on CA-190, passing Devil's Cornfield and skirting the 7,000-foot Tucki Mountain and 5,318-foot Pinto Peak before heading south on Panamint Valley Road. Brian was hoping we’d take Emigrant Canyon Road to Wildrose Road to shortcut and add some elevated joy to our packed adventure, but I chickened out. My heavy top case/Rotopax combo added too much weight up high, throwing off my balance when the roads became too soft.

We stopped to answer the call of nature and rehydrate at the intersection of Panamint Valley Road and Wildrose Road, a few passing RVs, trucks and sketchy vans driving by as I spied two Coors Light cans bereft of all color from the baking hot sun the summer before; it gets up to 130 degrees, obviously hot enough to bake just about anything left out in the sand.

Just south of the stark and depressing town of Trona – so named after the mineral trona, abundant in the lakebed – we encountered gale force winds, forcing us to lean into the crosswind like a MotoGP racer fighting g-forces around the Sepang International Circuit in Malaysia, screaming obscenities into our helmets to keep from going all Bruce Banner and Hulking ourselves to the pavement as we stopped at a Shell station in Ridgecrest to top off and head to Heritage Inn & Suites in Ridgecrest for the night.

We unloaded our bikes as the winds continued, albeit at a welcome decreasing intensity. After Brian lubed his chain we unpacked and enjoyed a well-deserved dinner and drinks at Ale’s Steakhouse & Bar across the parking lot. Tri-tip and a margarita never tasted so good.

Day Four: Ridgecrest to San Jose

Knowing that our final day on the bikes could take much more than the conservative seven hours or so that Google Maps was promising to cover nearly 400 miles, we set off in a driving rain on CA-178 West toward Bakersfield, retracing our steps over Walker Pass, Isabella Lake and Kern Canyon.

Duly geared up for the weather, we rolled into a heavy snow storm, waving to two perky cyclists on the side of the road, preparing for the same assault we were. Not one to miss a photo opp, Brian pulled over at the summit where the temps were below 30 this time, but grip was solid despite the slush quickly building below our tires on the descent toward South Lake where we stopped for gas and a bathroom break.

Isabella Lake was still dark under gray clouds as we found sunshine in Kern Canyon (below), stopping to enjoy it while we could. The next leg would prove to be a real whopper.

Bakersfield traffic was a bit hairy when we merged onto CA-58 West as the rain and hail deluged everyone unlucky enough to be out at the same time. I’ve ridden these roads before, the last time in warm and dry conditions with Jean riding pillion on our BMW R1150RT as we made the final stretch home from Barstow in late May 2017, from visiting family in Wisconsin.

On this trip, the rain subsided, but was replaced by the same gale force winds from the day before, maybe harsher, once we merged onto CA-5 North. Our objective was making it to Exit 278 in one piece, before heading 63 miles west on CA-46 to Paso Robles. I wouldn’t be surprised if our Conti Trail Attack 3 tires need replacing sooner rather than later due to uneven wear from riding at what felt like a 60-degree angle for that 32-mile stretch.

Nerves rattled, we stopped for gas at the 7-Eleven Valero, delaying the inevitable and unenviable prospect of riding directly into more strong winds to Paso Robles. We had families waiting for us at home, so we soldiered on, battling the elements as the winds kinda subsided after 50 miles. The rain lightened a bit as we pulled into our go-to 76 station near CA-101, where I fueled up and we enjoyed some warmth inside for 20 minutes or so. By this time it was 2:24 pm when I called Jean to give her an update. She was getting worried because nasty high winds were wreaking havoc all up the Central Coast into Mountain View. What would normally take two hours and thirty-five minutes ended up being closer to five as Brian and I decided to forgo more nasty cross winds on CA-101 and enjoy some goat trailing on Indian Valley Road through San Miguel, connecting to Peach Tree Road (below) which ends at CA-198. A slight dogleg left, then right on CA-25 North to Hollister, roads we’ve ridden during the day and in the thick of night.

The Road Less Traveled

Granted, Brian double checked road closures on his phone and declared our choice a solid one. We were trading a guarantee of high winds and a shorter duration on the interstate for possible mud slides, fallen rocks and flooding on the alternate route which could double the time it might take to reach home.

Daylight was on our side, and the rains slowed or stopped throughout our voyage northwest. We were cruising along at a nice pace, enjoying the scenery and lonely roads for nearly 90 minutes when, after dodging the aforementioned but passable obstacles, which hit a potential snag: a couple miles south of CA-198/25, the road was flooded the length of a football field, with slick muck coating the crumbled road.

We dismounted and Brian walked a third of the road to test the water’s depth. I joined him, and after talking through the alternative – turning around and riding all the way to San Miguel to tackle CA-101’s high winds – we decided ‘screw it’ and rode through it, snafus be damned.

Well, our risk was rewarded with forward momentum. The rain dissipated and we rode like Dakar champions on CA-25 North, enjoying the familiar curves and green scenery before stopping for a quick snack and bathroom break in Tres Pinos. My odometer ticked over 19,000 miles, reflecting the 6,000 I added a year to the day after buying my trusty Quota from McInnis, which brought a smile to my weary face.

Home

Our final gas stop was at the Chevron north of Hollister, where we high-fived, embraced, and rolled to 101, enjoying the light commuter traffic and mild wind as we both arrived at our respective homes around 7:30 pm, 1,207 miles and four days after departing with hopes for a good yarn to spin about my first Death Valley experience. Jean and Henri greeted me with an open garage door as night fell and the rain washed away some of the happy grit from an adventure I’ll always remember.

Who knew one could find so much life to live in Death Valley? Visit when you can.

What I Should’ve Left Behind

Light makes right with travel, and I typically over pack on a trip with new destinations during mixed weather forecasts and altitude. Brian was wrong in thinking I needed the Rotopax gas can, and I was wrong in bringing two books because we conversed about a range of topics easily right up until the lights clicked off for the night.

Otherwise, I may have overdone it with a box of protein bars and a bag of dried mangos, which were barely dented by our return. There’s a reason Brian weighs a scant 138 pounds: his appetite is tiny and even though he eats tons of miles.

Zabriskie Point - has been a must see for me for some time.

Check out the movie with same title with Jerry Garcia and Pink Floyd on score!!!