Recently, my longtime friend Steve Smith—whom I met working at a trade publication in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin in May 1988—gave me some constructive feedback on this blog. He suggested talking to someone who builds bikes without a sizable budget or corporate backing, and would I consider talking to his former co-worker Barry Weatherall?

“Barry was a former colleague at Rockwell,” Smith explained. “He quietly toiled as a creative director. One day I asked about his bike, having seen his motorcycle helmet always on display. He took me to the garage and showed off this awesome custom rig he had just finished.”

Smith encouraged me on to give credit to the builders you’d least suspect: those `without cool accents and exotic workshops in vitamin D rich locales; guys who build cool stuff right next to a high mileage Honda Odyssey minivan’.

So I did what my friend of 30-plus years requested: I called Weatherall directly, and introduced myself as a fellow pal of the affable Stephen H. Smith. We hit it off immediately, and this interview is the result of Smith’s sage advice.

Weatherall is a 53-year-old artist, father, husband and hobbyist motorcycle builder born and bred in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In 1972, his was the first Black family on their block near 20th and Hampton Avenue, not far away from Lincoln Park. He spent a good deal of time there, he tells me, running around in the woods that ran along the Milwaukee River.

“We lived across from big long fields with these really high power lines, so we had a ready-made football field/baseball diamond,” Weatherall explained. “My dad came from Mississippi to Wisconsin as a very young boy, but the country never left him. So he planted all sorts of fruit trees, grapevines, a vegetable garden in the backyard. We even had a squirrel that would come to the back door and Pop would let us feed him nuts.

“It was a cool place to grow up, a mix of being in the city but having peace and quiet like the country. I can remember being little kids and our parents letting us sleep outside at night. I now live in the house where my wife Liz grew up, built in 1924, near Capitol Drive and Green Bay Avenue. Her family also was the first Black one in the neighborhood, in 1962. She’s lived here all her life except our first year of marriage.

“Liz’s mom was from Virginia and moved back there; at first we rented to give her supplement income. We did a lot of repairs and remodeled, then bought the place when her mom got sick. So it’s been the family home for two generations, and has seen two sets of lives and stories.”

Give me a splendid overview of your artistic career and what it’s like living and creating and building in Milwaukee, Wisconsin now.

Ha ha, I don’t know about splendid! However, it’s had its interesting moments. My first paying freelance job (I think I was 14) was 5 drawings for my uncle, who did interior remodeling, for $250. I went to Milwaukee Area Technical College (MATC) for graphic design in 1986. I briefly went to Atlanta in 1988, job-hunting in summer in a black suit during a terrible 100° temp streak.

I worked at a few agencies and places, then decided to try my hand at freelance for a few years. Eventually, I worked at a Fortune 500 corporation for 23 years in varying capacities: freelance artist, graphic designer, project manager, trade show designer, eventually creative director.

My mentality was ‘though I had a supervisor to report to, the client was ultimately both my boss and my partner’. I treated what I did as if I was running my own business, so listening, suggesting alternate solutions and being attentive to needs became a habit, something that would serve me well later.

I remember meeting with Brooks Stevens in the early 2000s for two ideas I had in track and field. I wrote and illustrated a few children’s books. I taught adult education (desktop publishing) at Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design (MIAD) for a bit, and mentored kids at Milwaukee public schools. Did a few shows at local galleries; things like that kept me mentally fed.

But when I became a creative director I realized my true calling there was to lead, to be a mentor and teach others. I worked hard to hire untapped potential and foster talent in others, not focus so much on myself.

Eventually I moved on to other things, and now am very happy doing part-time work with a local company and freelance projects with some national clients, along with volunteer work.

Unfortunately it’s impossible to speak of creating/building here without acknowledging the ugly legacy of racism in Milwaukee, and it still lingers. Once, my dad said what many have told their children: ‘son, you’re going to have to work twice as hard to get half as much’. In the past I’ve come to understand the truth of that statement.

There have been some improvements, and it’s cool to see some positive developments in the art/design scene here. One of the reasons I went into the art/design field and persisted is because I wanted to help pave a way for others, even if no one remembers who helped pave that way.

I have friends that live right in my neighborhood who are amazing at what they do, but are humble people. One of the most recognizable muralists in the state and a Grammy-nominated music producer both live within a few blocks of me and their kids spent time at our house as they were growing up. I love that, it reminds me that creativity can come from anywhere.

Mostly, it’s good to be at a stage in life where you’re not worried about gaining approval or working some angle. Whatever happens, happens. I find the more I relax and take joy in what I’m doing right now the more truly good things come my way.

Before we start talking motorcycles, please tell me in detail all about the 1970 Ford Mustang Eleanor Mach 1 your father had that became yours.

My dad tells me he was never interested in many of the popular cars of the era, you know, the super long deuce-and-a-quarter type land yachts that were typical of the early `70s. The look of the Mustang got him, a muscle car with beautiful lines. Actually, Pop eventually had two Mustangs.

His first was the 1970 Mustang Mach 1 fastback that he bought used in 1972, with a 351 Cleveland engine (water pump cast into the block), traction lock, reinforced shock mounts/sway bars, deluxe interior package, hood pins/locks, the works. I used to love playing with the fast-cap as a kid: that gas cap you’d pop open and could fill the tank quick. Ford unibodies might have been great at the time for building lighter, faster cars, but Wisconsin winters will wreak havoc on all things metal.

I was 17/18 years old and felt a bit like Fred Flintstone: I inherited the car and the wind beneath my feet since I could literally watch the road through holes in the floor. Didn’t matter though: I had a set of slicks on the back and used to smoke the tires so bad bits of rubber would stick to the rear quarter panels. My best friend had his Olds 442 with a set of Parnelli Jones, I’d be in the ‘Stang and we’d go to a nearby industrial street which was the drag strip for everyone — a good straight 1/4 mile at least. Good times.

Around 1983, my dad got the one I really wanted: a 1969 Boss 302 (oh, that Holley Carb), very clean, that rightfully took up residence in the garage, with the 1970 being relegated to the parking slab since it was in decline by that time. We begged him not to sell it, at the very least give it to one of us!

Tell me about your earliest mechanical and hands-on automotive learning experience.

That’s hard to say. I’ve been told that from a very young age I was constantly taking stuff apart. I blame my parents for leaving tools within my reach, but I was notorious for disassembling any toys with moving parts that came into my possession. They realized they had an odd bird of a son: I wasn’t really as interested in purely playing with things as much as in the mechanics of how things worked.

So what do you do with an inquisitive, artistic left-handed introvert geek? You leave him to his own devices, and I truly love my mom and Pop for that. Anything electronic/mechanical and broken found its way to the room I shared with my older brother (which probably drove him crazy). I had no idea then but I was learning the principles of how things worked and moved.

Building models of cars and planes was cool, yet, it frustrated me that the end result was predetermined, you could change a paint style but that was about it. Thus began my making models from scratch: metal/plastic/wood/cardboard, anything I could find was fair game, the only requirement was that it had to have moving or detachable parts.

To be honest, I wasn’t the only one like that in my family: I remember being pretty jazzed to see my dad go to MATC to learn woodworking and build things in the house. Once he bought a grandfather clock in kit form. I watched him assembling all these parts and pieces, finishing the wood cabinet and then it WORKED?!! I was just amazed at his work and proud to say to folks 'my dad made that!'

From an automotive standpoint Pop’s ethos was: `if it can be done by you, do it yourself’. I’m fairly certain this was borne from the economic necessity of having a family with four young children to feed and clothe. So from say, 6 years old, I can recall hanging around the garage door watching my dad doing routine maintenance. By 12 years, I was out in the garage with him—I recall him pulling the carb because of issues and giving it to me—he told me to take a look at it. Not a whole lot of elaboration, just check it out.

Maybe he thought the thing was buggered and how much harm could I do. I laid out a sheet and started dismantling and cleaning this thing. He checked my process, fixed my missteps, put it back on and she fired up. That was definitely a defining moment: bringing a vehicle back to working condition was calming and gave me a sense of control.

However, Thaddeus Johnson was my automotive and mechanical mentor. He was a friend’s step-father and one of the best local wrenches; I didn’t realize till I was older that experienced mechanics were bringing cars by his home garage to be diagnosed for things they couldn’t figure out. He taught me several tricks: how to listen to/read timing and read a plug; smell for gas in the exhaust; the best way to access parts; or tell if a motor mount was torn by the way the engine moved.

I got my first experience in using an acetylene torch, working on a transmission, welding… it all came from him. He let us work on our cars at his place but even more importantly, he let us help him with cars he was working on, real work. Johnson treated us like sons, and never shied away from giving counsel or advice. When my wife and I were dating she was willing to get under the car and help with welding. Johnson pulled me aside and said: “See now, Barry, that’s the girl for you!” I miss him till this day.

At what point did fiddling with motorcycles enter your life?

I came to motorcycles later in life. When I was a kid, my dad and his cousin were on a bike and got shoved into a guard rail by a driver, cut up and hurt but made it out okay.

As a result, motorcycles were kind of a taboo subject growing up. My brother bought a motorcycle in my teens, a mid 70’s UJM (I can’t exactly remember) from a guy in Port Washington. He got a 20-minute lesson on how to ride it, plopped down his cash and rode home to Milwaukee as I followed in his car.

I considered riding but had one big issue: I was an adrenaline addict. I knew from drag racing locally that if I saw 150 mph on a bike speedo I was going to attempt it. Having known someone from my childhood who was decapitated in a horrible accident kept me from it for years; I wasn’t ready to ride until I could look at it differently.

So, after being married 14+ years, with three kids (9, 7.5 and 6) and 37 years old, I was ready. By now I see motorcycle riding as detox from the day—time to think about and process the everyday issues you might face. Liz didn’t balk, we simply agreed to some ground rules: take a riders course, ATGATT, and remember you have family at home so don’t be stupid.

I picked up a 1998 Yamaha VStar 650, a perfect introduction to motorcycling for me: shaft drive reliable, good clearance, easy to ride. I rode for a few months then started tweaking. I lost as much chrome as possible, put on a Hypercharger and a minor carb alteration, new bars, chopped down the front fender and repainted.

Next came two Honda CMT400s that were severely abused, $500 for both and more parts than I can remember. I really just wanted to learn how to strip a bike down completely and rebuild the mechanics, learn to wire, put together a bunch of things I’d been learning over the years. It wasn’t a gorgeous build; I realize I lean toward curvy, weird shapes inspired by the natural world and that can be a turn-off for some. But it helped me build confidence and skill, and someone DID love and buy it! A bunch of other bikes came, each one teaching me new technical skills.

Walk me through your Honda CB900F Eleanor build, from the original bike you bought to the finished customized machine.

I had just finished building a CB900C that I called The Stranger — this oddball cafe-ish two-seater that a few people ended up contacting me about because many attempts to cafe the 900C (hi/lo gear settings on a shaft?) just didn’t work.

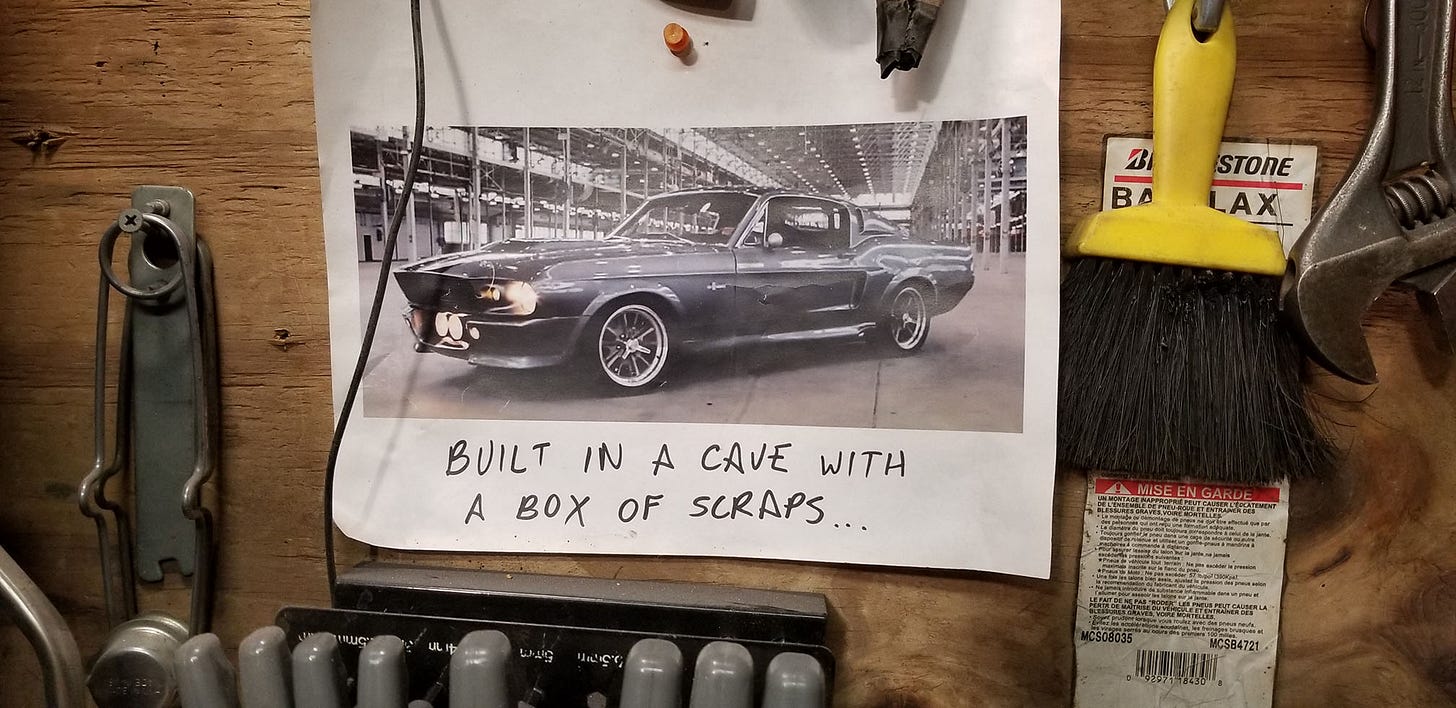

I also designed a system to run tubeless tires on my spoked rims and folks were asking for tips. After that build I needed a new challenge. My daughter has always been a huge fan of Chip Foose and OverHaulin’, a show we watched together. I talked about her Grandpa’s cars and how Foose helped create one of the most famous Mustangs ever — and the idea of paying tribute to both was born.

The CB900F I had sat in my garage for a year prior, from a local guy who sold me bikes on the cheap (this one, $550). It was a complete dog but the tank was clean, it had decent compression and the frame was sound. The Honda CB series were such influential bikes and “Mustang” is pretty much shorthand for “American Muscle Car”, a mashup of these icons and cultures made sense.

Fear is a big motivator for me—if I’m a bit scared by a challenge I feel like I’m on the right path. Having never turned a dual rear shock into a monoshock bike seemed like enough of a challenge. Design school taught me to get bad ideas out of the way quickly—so after looking at many, MANY homebuilt monoshock examples on the internet/YouTube that were obviously downright dangerous, I tried to learn the math/physics as best I could: sites like http://www.promecha.com.au/ helped me out.

I also saw a CB900F by Custom Wolf of Germany that was monoshocked, and the swingarm was close to what I had on paper. After working out the swingarm and frame dimensions, that sickening (and exciting) feeling of cutting into the frame began. My wife laughs anytime I say, “well, I’ve crossed the Rubicon now!” because whatever I‘ve just done, I can’t go back.

I approached the bodywork a little differently than past bikes. I usually make drawings, study and post them as I’m building and try to replicate the sketch. I made sketches this time and posted a picture of the Eleanor as well, but relied more on memories of what it felt like being in my dad’s car: the clock and gauges, feeling the curve of the fastback in the rear and the body panels, all that came back as a sort of a muscle-memory when shaping the bodywork. Try as I might to not build odd things, they always turn out that way.

The headlight assembly is an example of that—it references many details of the front of a Mustang. I would show my family parts I was making to which they’d say, “I’m not seeing it, I don’t get it”. It wasn’t clear until I did a rough assembly—then it clicked. To me, that’s the beauty of the car as well. These individual parts that might have been perceived as a little odd when put together, just come together, coalesce into something that works.

I try to make the personality come through in what I’ve made by hand. It’d be great to have expensive bolt-on accessories, but experience taught me to put that money into the engine.

Originally, I only rebuilt the top end and didn’t properly check the run-out on the cam chain and valves, and got inexpensive gaskets. It was a perfect storm to oil-starve and blow up an engine, which happened as I was running it hard down the freeway. Thankfully, I found a new one and did a complete teardown to check/replace anything I could afford with OEM/race quality gear. My recent change was to the front suspension, a definite improvement—which also changed some cosmetics on the bike.

Are you working on your next motorcycle? At 6’3” I’m curious to learn what bikes you’re considering.

I’m open to suggestions! My initial thought: something with EFI, probably in the 2010-15 era, that can be had for a reasonable price. I feel like for my next personal ride I may stretch out my legs, with forward controls. A friend I ride with has a 2018 Indian Scout bobber, and I’m looking at their Chief Dark Horse.

I’ve also been talking with my brother, who just retired from Harley-Davidson, asking him for reliable platforms to build on. Whatever it is, I don’t want to act like it’s precious because it may be a newer model: a fender chop and a little paint won’t cut it anymore.

I’m still building an 1985 Honda VF700 Interceptor that will be for sale. I’ve modified the frame for a new longer swingarm, started a bunch of metalwork and changed out the front-end so far, and have some interesting plans in the works. But it’s definitely a bit small for a guy who likes Culver’s burgers as much as I do.

My favorite article so far!